Here is the full, translated letter from R’ Yitzchok Nachum Twersky of Shpikov to his friend Jacob Dineson1. Part of the famed Twersky family, and a direct decendant of the Maggid of Chernobyl. The letter was written in 1910, when Twersky was 22 and about to be married off to the daughter of R’ Yissachar Dov Rokeach, the third Belzer rebbe. The letter reveals the inner struggle of a Jew grappling with his identity in the quickly modernizing world.

Dear friend and beloved author, Mr. Jacob Dineson!

For a whole year now I have been endeavoring with all my will and strength to write your honor a letter. For there is none other to whom I can lay bare my mind and reveal the secrets of my life or, better, the gloomy life of my environment; and there is none other who possesses a warm, sensitive, feeling heart, that might fittingly resonate to all the spasms and tremors of my soul. For behold, throughout that whole year, since becoming acquainted with you and your gentle, delicate soul, I have been consumed by an innermost need to correspond with you, to reveal to you all that is hidden in my heart, to unburden before you all that is concealed and confined in my soul. I imagine always that my soul will then find solace, unburdened of a heavy load of stones. My stifled thoughts and unspoken words will find proper expression in my letter, and they will surely achieve their object, for in your honor they will find a person who will understand them and sense them.

Thus I thought, and thus I desired all year. But not merely one thought and one desire do I harbor in my heart and hollow them out a deep grave therein. Much have I experienced in such matters. All my life is one long chain of suppressed desires, concealed ideas, shattered cravings and wishes. And indeed I was forced to do so with this particular desire as well. Thus dictated the circumstances of my accursed life, and who shall oppose them.

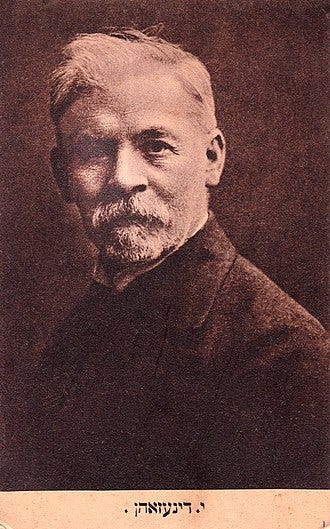

But now the opportunity has beckoned, and I have sent you my portrait; far be it from me to deny that, apart from sending my portrait to you—a person whom I think of as a dear and highly respected friend, deeming it a great honor for myself if my portrait should be in your possession—apart from that, I had another, covert, intention. I wished you to see and recognize all the duality and two-facedness of my world, to apprehend the great difference and distance between my inner world and my outer world. I thought, therefore, to let your honor gaze at my portrait, see all the wretchedness and ugliness in my clothing, and conclude there from by logical analogy as to the whole picture, all the external trappings of my life. I wished you to recognize all the darkness and gloom around me, to inspect at once my external appearance, in all its fearful darkness. I will then come to your honor in my letter—for I felt that, despite all the obstacles, it will no longer brook any delay; for as lava bursts forth from a volcano, so shall my letter burst forth from the conflagration of my blazing soul, surging forth and carrying all obstacles before it—then shall I stand before you in the fullness of my inner portrait, remove the veil and discard the black mask from my face; I shall reveal to you the depths of my soul, the light hidden there. And then a new world will open before your eyes, a world full of song, a world full of light and radiance, a world full of sublime ambitions and lofty hopes. In contrast, I shall also picture for you my second, other, outer world, in all its blackness—the blackness of the portrait is naught in comparison. I shall not use many colors, nor heap words upon one another. Only a window shall I breach into that terrible, awful gloom, to enable its darkness to be seen in all its horror; and then, against the radiance and brilliance of my soul, the darkness in my outer world shall be seen in all its terrible obscurity; and against the background of this awful, gloomy darkness, the light of my inner world shall shine forth in all its radiant loveliness. And then, when your honor should perceive the terror in that darkness, and the magnificence and magic in that light, in all its fullness and depth, then shall you understand the extent of the sorrow and the pain of that welter and chaos of light and darkness or, better, of the light that is usurped by darkness; and then shall you apprehend the whole depth of the rift in my soul.

Such was my intention in sending you my portrait, and that is what I planned and wished to do. How great then, was my amazement that your honor had truly understood, or better, sensed, all this even before I had time to write you my letter, and perceptively expressed this in such fitting words in your letter to my sister.24 Nevertheless, there is much, very much, that remains locked away and concealed from you in my soul, concerning which you wish to know, and you address this question to my sister. These words and questions of yours have further fanned the flames of my craving to write your honor a detailed letter, in which I shall present myself whole and all of my environment without embellishment. That I shall do in this present letter.

But before proceeding to the main body of my letter, let me forestall your complaint to my sister that she disregarded your warning and admonishment not to show me your letter. Presumably, your honor thought and supposed that your words would pierce my heart like daggers, and therefore was loath to distress me. Please believe, then, what I am now telling you, that, quite the opposite, the impression your words made upon me was the reverse of what you might have thought. Your words could not distress me, because they in no wise surprised me. I might have been aggrieved only by words that surprised me, by new words, the like of which I had never heard before, new ideas the like of which had never occurred to me. For example, had I been calm and composed, stoical about the conditions of my life, finding nothing amiss with them, and your honor had addressed me with sharp words and proved the reverse to me, then surely would the pain have been great and awful, the distress deep and profound. For with such words your honor would then have been demolishing all the lovely castles and magnificent towers that I had erected in my mind, evicting me from my own world where I had already found myself a good place and thought it calm and restful, by showing me that my own world is not good and not beautiful, that there is another, more beautiful world, more fascinating and appealing. Like a man sitting in the dark, having never seen light in his life, the thought having never occurred to him that darkness is not good but harmful, and suddenly another person appears and opens up for him a window into the light, to show him its goodness and beauty— would he ever be able to reconcile himself to his darkness?

But that is not my situation. Never have I been content with my narrow, dark, gloomy world, and always am I aware of the contrast between the great, beautiful world and my tiny, ugly world. And always I say, ‘The place is too crowded for me.’25 Could your words astonish me, of all people!? Could they cause me grief and pain!? On the contrary, I felt myself consoled by your words, realizing that a great man like yourself sympathizes with me and feels the wretchedness of my world. The very opposite—had your honor not told me such things, had you proved to me that even a life like that which I am living is not bad, then should I have felt myself wretched and depressed. Could there possibly be any person who would say about such a terrible life that it is good?—So let you honor’s mind be at rest. You have not caused me any grief; on the contrary, I owe you gratitude for your letter and your sympathy. Therefore, my sister, who knows me well and who well understood your honor’s intention in your admonition, knew that there was no point here for such concern, and allowed me to read the letter. And that is, then, my answer to your letter.

Does your honor know the state of Hasidism in our time and in our country?—In our country in particular! For in Poland and Galicia the situation is very different. Do you know its essence, its content, and its nature? I shall not be far wrong, I believe, if I answer in your name: “No!” Perhaps your honor is familiar with the state of Hasidism in the early days of its flowering and its growth, in the time of the Besht and his disciples, and later too, in its heyday, in the previous generation, when Hasidism itself was still a kind of “system,” and the Zaddikim who bore its banner aloft were still imbued with the spirit of Hasidism, still exerting considerable influence on the people.

As to Hasidism and its standard-bearers in those days, surely that your honor has read the many monographs that have been written about them in our literature. Surely your honor has personally perused the books of Hasidism and extracted the precious pearls scattered here and there in that literature, among the heaps of ashes of hallucinations and nonsense. Thus your honor surely knows about the origin of Hasidism and its state in the first and second period [of its existence], although your knowledge is not perfect but involves some errors and misconceptions; for hearsay is quite different from eyewitness evidence, and a person who has been reared and educated in the innermost circle of Hasidism, with masters of the movement all around him, familiar with the development of the movement from its beginnings to this day, with all its faults and merits, cannot be compared with a person born and reared in an environment foreign to Hasidism, all of whose knowledge is derived from books alone, from legends, not from life itself. And most of the books, in particular those of our latest authors, who have begun to deal in recent years with Hasidism as a system and a movement, are so remote from life and from reality; they are so openly tendentious that a person consulting them to trace the roots of Hasidism from them alone, be it only through popular legends which are mostly very beautiful but far from the truth, might liken the false luster of rotten wood to a brilliantly glittering gem, and an ugly sight in this movement to a splendid, charming revelation. But nevertheless you have at least some idea concerning the Hasidism of those times. But as to the Hasidism of our times and our provinces, surely you have heard nothing, for the literature makes no reference to it at all, and in life you are very, very remote from us. Your honor resides in Warsaw, the capital of Poland, where Hasidism still has all its power and its influence is still tremendous. So let me describe to you, quite briefly, the state of Hasidism here, in our province, the province of Ukraine.

In saying here “Hasidism,” I use a metaphorical name, for that name is entirely inappropriate to present-day Hasidism and has been so for some twenty years, since my grandfathers, the famed Zaddikim of Skver, Talne, and Rotmistruvka—all my ancestors—and their brothers, the standard-bearers of Hasidism in our province, who commanded thousands of faithful Hasidim, died or, as the Hasidim say, departed this world. Since then, the light of Hasidism has dimmed and its glory has gone into exile, and it has atrophied, continually declining, continually diminishing from day to day, until now it is little more than a debased coin, a name devoid of real content.

The reasons for this are many, more than can be listed here, for in order to explain them one would be obliged to delve deeply into the history of its development from its beginnings until today. But such is not my object here, for not to tell the story of Hasidism have I come, but only that which affects my person, my life history. Nevertheless, there are two main reasons: First, my ancestors did not leave after them sons like themselves, men of understanding and intelligence, who might influence and impart of their spirit to the congregation of Hasidim. [Their sons were] either men who, though indeed great masters of Torah and pious, proficient in the works of Kabbalah and Hasidism, were weak, exhausted, and uncivilized in all their ways. Little knowledge have they of the world and of men, they lack any sense of beauty; ugliness rules all their doings, their clothing, their speech, all their motions; Or they were common men, faceless and nondescript, neither masters of Torah nor knowledgeable and virtuous in the ways of the world, their only claim to fame being their ancestry. That is one reason.

The second is the intellectual development of our province. In the last twenty years, our part of the world has taken such enormous steps forward that it has almost overtaken even Lithuania.26 A new generation has arisen, a generation that knows not—and does not want to know— its old ancestral traditions, a generation that thirsts for [secular] education and longs for freedom. This young generation has influenced the older generation and imbued them with its spirit. The generation looks completely different. The old type of pious, patriarchal Jew of the previous generation is no more, almost completely disappeared, displaced either by the completely free-thinking Jew, or by the simple, bourgeois Jew, neither very pious nor free-thinking, just an ordinary Jew, no longer with the perfect, simple faith of the Jew of the previous generation. While there are still many old people of the former generation, but solitary remnants are they, few in number in every city, and they have no influence on the march of life, a few lost souls. They sit, each in his own corner and shaking their heads in disgust, heap their curses upon the new generation that has left them behind, advancing far, far beyond them. Upon such arid ground, of course, Hasidism cannot possibly bear fruit, and so it has gradually degenerated, until there is almost no trace of it here.

Those old Hasidim, in whose hearts the memory of the first Zaddikim, the forerunners, still live, could not communicate with the sons who succeeded them. Sorrowfully they look and gaze from afar upon those who have come to occupy the throne of their masters and teachers. In their grief, they have retreated into themselves, delving deeply at least into the books of the Zaddikim, contenting themselves with tales and memories of the good old days, that they tell each other upon meeting. And a new generation of Hasidim, who do not recall the “founding fathers” and will make do with the sons, has not arisen, for the new generation is far removed from Hasidism.

In short, that first Hasidism, whose name at least was fitting, has wholly perished. Instead, a new Hasidism, which might more precisely be termed “wheeling and dealing,” has appeared. For the new Hasidism is little more than shop-keeping. A Jew who enters the Rebbe’s house does not come to be admonished, to learn some virtue, to hear a good word, for such Hasidim are no more; they come to the Rebbe in his capacity as a wonder-worker, begging him to demonstrate his miracles for them, to save them from misfortune, in exchange for the money they pay him for the miracle.

And it is self-evident that such people are most brutish people, whose very boorishness is their Hasidism. For lo, the great legacy our ancestors bequeathed us, all the virtues of that heritage—albeit for those who considered these qualities as virtues—all its splendor and magic, have been totally swept away. And this alone the house of the Rebbe in our parts retains as a heritage from our ancestors—all the refuse left over from its ancestral customs. All the wretchedness and ugliness, the idiotic costume, all the wild motions and customs, these alone remain to them, they are sacred and untouchable to this very day. Such is the state of Hasidism in our time and in our province, such are the Hasidim, and such is the image of the house of the “Rebbe.” And in such a time, in such a house, was I lucky enough to be born.

I imbibed piety with my mother’s milk, I was reared on the wellsprings of Torah and Hasidism, and no foreign spirit penetrated our home to dislodge me, God forbid, from my place. But nevertheless, since the day I attained maturity I was imbued with a different spirit, I was different from all around me. Of course, that was within the hidden depths of my mind; outwardly—the less said, the better. I felt that my world was small and tiny, constricted, choking and strangling me; and in my innermost being I longed so much for a different world, a beautiful, wide world, that would give me enough air to breathe. I despised the people around me, loathed their way of life, and was drawn upward as if by a hidden force. There, in the infinite expanse, above the swamp in which I was immersed.

How did such ideas occur to me even in my infancy? What moved me to despise my surroundings, to hunger with all my heart for a different world? I myself know not, for who knows the way of the spirit? But one thing I do know: I have a delicate, poetic soul. A yearning soul, that could never reconcile itself to its gloomy, dark condition, but has always longed and pined for another life, more beautiful and far more interesting.

I remember the impression made upon me by my frequent hikes, when in my youth I would go out in the summer, with my teacher, to the forest outside the town, along a path meandering between green meadows. Leaving the house, with its all-pervading stifling air and stifling spiritual atmosphere, and my encounter with nature. Free, living, blooming, nature; the enormous contrast between our house—our house in particular—and Creation. All these had such an enormous influence upon me that in the first moments I felt drunk, intoxicated with life and its joy, intoxicated by the magnificence and magic of nature. I forgot the whole world, forgot the house and its duties that I had left behind, the narrow surroundings and everything that I hated, and was seized by only one strong sensation—a sensation of pleasure and life. All those sleeping life powers within me, that had flickered deep within my heart, burst forth with overwhelming force. I desired then to embrace the whole world, to kiss the world—the fields, the forest, the birds flying over my head—with one kiss. To satiate my burning, life-desiring soul.

But this mental state was not long-lived. Slowly but surely, the joyful feelings began to evaporate, to be replaced by muted sorrow. My memory began to resurrect my duties at home, my way of life, the chains that shackle my spirit. I remembered that no son of nature am I, to rejoice in nature’s joy is not my lot. I remembered how far I am from nature—the very opposite, I am far removed from free, honest, and simple nature, which knows no cunning or falsehood; for I, hypocrite that I am, dissemble and deny. I do what I desire not to do, say what I think not, and I am entirely unnatural. I love nature, all that is good and beautiful, but I myself, in my dress, my actions, my movements, embody the antithesis of both good and beautiful. Such sorrowful thoughts and bitter feelings filled my mind as I ended my outdoor walks, returning home always with pain in my heart to discharge my “duties” and to live my

“life.”

Thus I grew up and thus I lost my way, my heart a burning hell and fiery furnace, but outwardly behaving as if everything was as it should be, a child of my environment. And so I became what I am now.

Much Torah have I studied in my life. Much have I racked my brains over weighty volumes of Talmud and legal codes. I have also pondered books of our philosophers, kabbalists, and Hasidim. Thereby have I earned a place of honor among the Torah scholars of my town, and acquired a reputation throughout my neighborhood. And all the Torah scholars and the Hasidim—of the old type, proficient in the books of the early Hasidim, who served under the old Zaddikim—come daily to visit me. One comes to me troubled by a weighty problem of the Talmudic text that he wishes to discuss with me and hear my opinion of the matter; another comes with a perplexing passage of Maimonides; and yet another wishes just to sit with me, regaling me with his tales and recollections of the early Zaddikim, to hear a pleasing adage from suchand-such a book that I have seen, and to tell me something of what he has read and seen. What shall I tell your honor? The sufferings of the dead in the grave, if such indeed exist—as the faithful tell us—are naught compared with the mental anguish and heaviness of heart that these visits occasion me.

I am young in years, bursting with youthful energy and life forces. My ideas are ideas of life, and my ambitions, ambitions of life. But my bitter, harsh fate forces me to spend most of my days among old men— whether old in years or in attitudes, what matter?—mummified, dismal, whose God is not my God, their views not my views, all their thoughts, goals, and desires foreign to me. In such circles am I obliged to spend my days, to partake of their rejoicing, to sympathize with them in their sorrow and grief, to be considered as one of them.

Imagine, if you will, your honor, the scene: a beautiful, clear, summer’s day, the sun bathing the whole universe and world in its rays. Waves of light stream through the wide window into my room, and I am seated at my table, the thick tomes open before me, but my thoughts and feelings are not for those tomes at all. I glance outside, I see the blue sky above my head and the abundance of light outside; and hushed, secret, longings seize me. I pine for, dream of a beautiful, magical, world, under a pristine pure, blue sky, its brilliance unmarred by the smallest cloud, radiant with brilliant light, not the slightest shadow darkening its expanses. Thus I sit pining and dreaming, my imagination bearing me on its wings to the farthest reaches. Suddenly—a knock at the door. I open, and there before me stands the local rabbi... He wishes to delight me with a novel point that he has made in his Torah studies. And immediately I am torn away from my pleasant dreams. It is as if I had fallen all of a sudden from the heights of magical imagination to the depths of bitter, black reality. And then the sharp, hair-splitting, discussion begins, objections and solutions flying back and forth. An onlooker might believe me wholly engrossed in this give and take; but how bitterly is my heart weeping in secret, for the ruin of my world, for the theft of my youth’s dreams, that I am forced to exercise the best of my powers and talents in empty, dry, casuistry about the minutiae of the dietary laws, in conversation with Hasidim about the Divine Presence in exile—by God! Do they understand, feel, the meaning of “Divine Presence?” And what is “exile?!”—or about so-and-so the Zaddik who performed such-andsuch a miracle, and some Rebbe or another who worked some kind of wonder.

Well I remember what I read in Dr. Berdyczhewski’s book The Hasidim, where, after heaping copious praises on the Hasidic theory, he concludes with a heartfelt cry, “May I be so lucky as to share their portion!”—that is, that of the Hasidim. And, recalling that exclamation, I cannot hold back my laughter. Indeed, Herr Doktor! How right you are!

But how convenient it was for you to utter this exclamation, on your lofty chair at Heidelberg University, far removed from the Hasidim and their masses. But what would you say if it really fell to your lot to be among them always? Methinks you would have spoken differently then, a very different call would have issued from your heart, and together with me you would have cried, “May I be so lucky as not to share their portion.”

Duplicity, two-facedness, the cleft in my soul—whoever has never experienced them cannot possibly imagine their bitterness. Is there any greater sorrow, stronger pain, than the need constantly to strangle one’s dearest thoughts, one’s most sacred feelings, lest they be detected outwardly, God forbid, and some harm come to one? Constantly to see one’s most cherished hallowed ideas trampled by others, and to profess happiness, as if in agreement with them?

I constantly have free thoughts, but I am obliged to observe my ancestors’ most minute stringencies of observance; I have good taste and love beauty, but I am obliged to wear the clothing of the uncivilized: a long silk kapota down to my feet, a shtrayml of fur tails27—that is the “badge of shame” imposed upon us by our haters for generations, which has become holy to us Jews, enamored of the hand that beats us—with a skull-cap beneath it, and other such “ornaments” as well. What would your honor say, were you to come suddenly, not knowing me, and see me standing among the praying congregation, clad in this tawdry finery, swaying and praying, what would you think of me then? Surely you would hold me to be ultra-Orthodox, a devout fanatic. Never would it occur to you that I am different from all around me, and that under this showy trumpery of clothes hides a beautiful soul, dreaming, longing, and pining, just as it would never occur to any of those who know me— with the exception of those of my young friends of like mind—and who consider me to be a Haredi. And how my heart aches when perchance I hear my praises sung, whether in my presence or otherwise, that I am a God-fearing, perfect person. A terrible thought pierces and gnaws my mind: What is this? What am I? Is it possible that I am naught but a hypocrite, a sham? Am I permitted thus to deceive people?

Thus do I live out my life here, a dark, gloomy life, without a spark of light, without a shadow of hope, all darkness about me. Nevertheless, even in my life here, despite the all-pervading darkness, sometimes a glimmer of light breaks through. At times of leisure, free of my environment and its obligations, I repair to the “left wing” of our home, to my sisters.28 Then does a new world open up to me. I cast off the dust covering me, distance myself from the filth, from the grime in which I am immersed all day. Some freedom indeed reigns there, in contrast to the chains and shackles in our home, freedom that my sisters have earned “with their sword and with their bow,” freedom from that fine company that surrounds me all day. There I meet young friends and acquaintances, and we read and speak of life and literature. In brief, there I live my real life, there I remove the mask from my face, to be what I really am, without dissembling. Although even there the shadows overcome the light—as you already know well of this “life” from my sister’s letters— and even there I cannot breathe freely, even there the air is full of sorrow and grief. But in comparison with my own “life” in my room, that too may be called a life. So here there is still a gleam of light illuminating me within the darkness.

But what a terrible thought, to think now where I am going. To the blessed town of Belz in Galicia! For I have to settle there, in their “harem.” I underline that word to emphasize my intention, that I am being married by coercion, against my will. For me [to marry] a woman from there—my gloomy life here, with all its black darkness, will pale in comparison with the life awaiting me there. First, I am marrying a woman from there, a woman who has been destined these six years to be my bride, but even so I have never ever had sight of her face and I have not the slightest idea of her, her beauty, intelligence, and understanding. And with such a maid, of whom I know absolutely nothing, I am now being led to the bridal canopy!

Can your honor, a cultured person, living in the twentieth century, possibly understand and conceive of this? When I think on it—and when do I not?!—I am seized by trembling. I am entering a new period in my life, the most important period in human life—and whom have they given me as a life partner, to be my wife, with whom I am to spend the rest of my life, sharing my happiness and my sorrow, my joy and my woes? I know not. One thing only do I know, that there is a certain town somewhere, Belz by name, and there lives a young maiden, as unattractive as can be—this I have indeed been told by people who have been sent to see her visage—and she is “my bride.” What is the sign that she is “my bride”—that I know not, but that is what people are saying, and there is the proof, for now I am being led to the bridal canopy with her. What is the nature of this maid? That I know not, and neither do all those who have gone there to see her and have tried to investigate her character. For how much can be determined from fragmentary information, acquired in a few days, and moreover by a stranger, who knows not what to say and what to ask, and I cannot extract from him a proper sentence about her? Having now to approach her to make her my life’s partner, I am relying on accident. Perhaps accident has indeed ordained a suitable match for me. And it is equally possible, very easily, that it has matched me with my very opposite. At best, however, what might I expect of a “Belzian” maid? What spiritual development could she have had in such an environment, in such an atmosphere, where such a simple, innocent thing as learning to write is a serious offense in a young maid, at most a luxury. “A woman’s wisdom is confined to the spindle”...!29 What hope is there for me, why should I delay any longer? The greatest fortune would be if, at least, she were not already entirely imbued with the usual Belzian ideas and desires, if her heart were still lively and open to other human ideas and desires as well. And if the saplings of humanism that I shall try to plant in the soil of her heart, bear fruit and do not find arid ground—that would be my greatest happiness.

That is one of the “good” things awaiting me in the near future. That is the central point, and if the center is naught, what could the circumference be?—Even less than naught.

And the circumference, the environment, what of it? If ten measures of extreme religious fanaticism, ignorance, and vulgar stupidity came down to the world, Belz has received nine, and one the rest of the world. If your honor should wonder at my non-modern dress, being so remote from this ancient world, he will marvel a thousand-fold at the Belz customs and will despair of even understanding them with his mind. Let me tell you now a little of their capers, a drop in the sea of their deplorable ways of life, for my feeble pen is powerless to provide a faithful, complete picture of their doings. That would be a task worthy of a witty belletrist’s pen. May your honor gaze and marvel, hear and not understand, and you will think that I am leading you far, far away, from the cultured lands of Europe to the uncivilized lands of China or India, for there, only there, can one view other pictures like these.

In addition to the stringent and precautionary measures that every Jew has around him, Belz have adopted further such restrictions that have no sanctified source, nor have they issued from the legal decisors, they originate solely in “ancestral” customs. Left and right, upon one’s every step, one finds and stumbles over a custom established by “the ancestors.” So uncivilized, so obstructing and disturbing the free course of life are these customs, that one cannot imagine how a person—even a person like myself, accustomed to strange life practices and precautions, but who thinks always of one way of life—could survive in such a stifling atmosphere, in which every move, every wink of an eyelid, every innocent thought, any action, the most proper action imaginable, in line with Jewish Law, will be met with ponderous objections, on account of “custom.”

Here are some examples. The bridegroom on his wedding day must shave his head with a razor. And the bride? That goes without saying, for all women there have shaved heads, for that has been decreed by custom.30 And a wig—which in our provinces is the custom even of saints and pious people, and most women go about with their hair uncovered—is considered there a greater abomination than swine. In all the town of Belz you will not find even one woman wearing a wig on her head, but all wrap their shaved heads in a kerchief. And on Sabbath days and festivals they wear a kind of old-fashioned veil, which, if I am not mistaken, is the very veil with which the Matriarch Rebecca covered her head. [The veil] must conform to this fashion, it cannot be otherwise, and all according to the custom and decree ordained by the ancestors of my future father-in-law,31 the Zaddikim, the leaders of the town and its environs; and he—my future father-in-law—being their representative, enforces them, and by virtue of his tremendous influence not one tittle of them may be omitted.

Picture, your honor, if you will, the following scene. Imagine that myself and my “intended” are being pictured. A young couple—“He” has his head shaven, and “She” has her head shaven. He wears a shtrayml and a skull-cap on his head, with all the other finery—as you will see later—and she wears a magnificent scarf on her head with all other female trumpery from Chmielnitzki’s times.

A nice caricature! Good candidates for a museum of antiquities! Were it not that this matter concerns myself, I could laugh most heartily at the sight of such a picture. Unfortunately, however, the matter is so close to me, so relevant to me, that it may arouse in me not laughter but only tears, tears over my ill fortune, the fortune that fate has declared for me in this inhospitable land.

Trousers are now fashionable, but anything fashionable is strictly forbidden there. So the men wear long kapotas down to their feet, and the kapotas must be sewn from a single piece of fabric, and they may be from any kind of fabric, from silk to choice linen. But not a woolen weave, which is forbidden for fear of sha’atnez.32 And under that long uniform they wear their long winter underwear visibly, white as a “pavement of sapphire.”33 And their ear locks are long, O how long— down to the navel and more, for that is an immutable decree: “It is forbidden to cut the ear locks of the head and to shorten them, from day of birth till day of death!” And those long, thick, ear locks, spread over the face and swaying here and there, wherever the wind blows them, and they seem as if attached by glue to the white, shaven, head—and why is that?—To mar man’s handsome visage, “God’s image.” And in this beautiful costume one has to go about all day, not only during prayers, girded with a sash.

No lamp will you find in their houses, only candlelight to illuminate the dark. Now in this generation of ours, a generation of great technical discoveries, a generation served by electricity day by day, when the human spirit, unsatiated, is blazing new trails and new paths, striving hard to find new inventions. In this generation, at this time, there is a dark corner, in the heart of Europe, where even a simple lamp is not yet used, even one that might today be considered an antique, and the dark light of a tallow candle satisfies them.34 O, people who live in darkness! Beautiful furniture and household utensils are a luxury. A mirror is considered as leaven [on Passover], to be banished from the house. Galoshes over the shoes are an abomination—“Everything that walks on four is an abomination,” an explicit proof from the Bible!35 A newspaper, even in Hebrew, or in Yiddish—not to speak of a volume of the new literature—is condemned to be removed and banished.

Those are some of the uncivilized customs that prevail there, a few small details, which your honor will be able to put together and thus to conceive a full, accurate idea of all their ways of life there. And these customs are supervised by my future father-in-law, the Grand Inquisitor,36 who watches over the slightest move of the members of his family, his town, and his Hasidim in general. And woe betide any person who dares to infringe even one of all these “customs,” who deliberately disregards one of them. He will be pursued and beaten with cruel wrath, with all their burning, wild, fanaticism. They have one refrain: “Eat and drink, study and sleep,” for that is the whole man!

They are far from the world and from life. The voice of the sun’s orb, traversing the heavens and announcing that time is passing and will not stand still, that the times are changing and with them man too—they hear not that voice. They are frozen, fossilized, standing constantly on the same level as our ancestors in Poland three hundred years ago. And if they have developed, if they have taken a step forward and gone farther than their ancestors, they have done so only in the sense that they have heaped more restrictions on their ancestors’ restrictions and added stupidity to their stupidity. That is the blessed Belz, such is its visage, in miniature. In that Belz, in that locality, am I to settle now.

And if all the happy things in store for me there were not enough, my father-in-law-to-be is a strong, hard man, one who likes everything to proceed according to his will, strict, intimidating all those around him, à la Stolin—your honor is surely acquainted with the picture of Stolin through my sister.37 I shall have to submit to him and bow to his authority, suppressing my will in favor of his. And I am so enamored of freedom—I do not speak anymore of freedom in its broad sense, but at the very least freedom for myself, in my innermost soul, not that another person should trample my soul with his coarse sandals—I am so unable to relent, to submit, to bow to authority! Those are my great prospects for the nearest future. Even now I drown in mud up to my neck, and now I am being dragged to drown entirely in mire, in a pool of sewage. Indeed, a terrible idea, and the reality is seven times worse!

I know that, upon reading this confessional letter of mine, your honor will think of many questions that you will labor to solve, and first and foremost, one central question that pervades the whole letter: “If you are so remote from and abominate the life that you live; if you so feel and understand how terrible the new life that is awaiting you, if you so understand the depth of its tragedy—who is it, what is it, that forces you to persist in that miserable life? Sever, in one blow, the bond that binds you to it, break out into the great, wide, world, that you so love, for which you so yearn and pine!”

Yes, yes, your honor is absolutely right in that question. That is the question I am asked by many of my young friends, who cannot understand my mind, to whom my psychology is foreign, who only see the terrors of my outer life. They, not knowing my mind, ask me such a question; I dismiss them with a brief answer that says nothing, and they retreat. But before your honor I shall bare my soul, explaining the obvious truth to you: a sacrifice am I, a sacrifice on my mother’s altar.

As difficult as it is for me to sever the thread of my life, as helpless as I am in that respect, nothing would hold me back, nothing would withstand my burning passion, the fire of my aching soul, and I would indeed have taken such a step. With my last remaining strength I would cast off these shackles, abandon my home, my family, my place of birth, all the habits I have accumulated since my youth, and travel to a big city, to study there, complete my education, to live another life. I would reconcile myself indifferently to poverty, sorrow and suffering. I would accept everything in love, provided only that I could save my soul. Nothing would prevent me—save just one hidden power in my soul which is stronger than all these combined, which holds me back with tremendous force and will not loosen its grip—the power of compassion. This feeling, which I have to a high degree, is what will not allow me to carry out my plan—my compassion for my beloved mother.

This wretched soul, who has had nothing in her life, all of whose life is one terrible tragedy, and I, I alone, am her only hope, her heart’s desire, I am her comforting salve. My sisters have never given her much pleasure, only in me does she put her trust, I am her sole support in her life. So how could I bear to see the evil that would befall my mother, how could I, with my own hands, shatter her only hope and cause her such overpowering disappointment, such great sorrow and grief? I shall not investigate the question logically, whether that is how things must indeed be, if I must indeed abandon my future world, which is still beyond my reach, for her world which is already old and withered, for her life which is already behind her.

I shall not investigate—because I cannot investigate. Where emotion reigns, there is no logic, everything is molded by instinct. That is why I have suffered in silence till now, and that is what now forces me to take this new step of marrying into Belz and settling there. Why do I have to settle there, of all places? Why can I not live here even after my marriage? For a very simple reason: My parents lack the means to support me, to sustain me and my wife in their home, to supply all our needs. So I have no choice but to live there.

To think of the possibility of leaving there and making my own way, that too I cannot do, for if so there are only two roads open to me: To be a [Hasidic] rebbe, or to be a rabbi. The first alternative is of course out of the question. And the second alternative too, apart from the fact that it is not to my liking, it could never be realized, because to be a rabbi I would need authorization from my future father-in-law— who by then would be my father-in-law—and if he were opposed, I could of course do nothing to oppose him, for he is stronger and more influential than I, and no community would accept me against his will. But I would never receive such authorization, because he wishes to keep me under his wing for a few years, who knows how many? And even were he to grant me authorization, I would then have to be a “rabbi” according to the Belz style, so what would I gain? Once again the same slavery, the same wretchedness and the same ugliness.

So I have absolutely nothing to hope for, there is not a single glimmer to light my way, the way of my future, only darkness, awful darkness, profound gloom await me. And when I throw myself into the waves, the angry, flowing, current of life, where shall they carry me as they flow? I know not. I hope that at long last the waves may bring me to some shore, for if not for that hope, how terrible life would be! I hope that this Belz will be no more than a way station, a stopover on the way to a more beautiful, better life, to that life that I so desire and yearn for!

Indeed a difficult stopover, but nevertheless only a stopover. One cannot reach Paradise without first passing through the departments of hell.

Belz as a way station—how is that to be? Listen and I shall tell you. As long as I am here under my mother’s authority I can do nothing. I stress, always my mother, not my father, for my father is cold-tempered and will not feel such pain. But my mother—she is a warm, feeling, person, and I must take her into consideration. Were I to take such a step as I intend to take—to depart from here, from her, before my wedding, she would be burdened with all the responsibility; all the “What will people say?”—the questions she fears so much—would fall upon her. The noise, the public commotion, would be too much. Here I was, and all of a sudden—I am gone. The embarrassment, the uproar, the questions all around, from all the townspeople, all our acquaintances, the talk, the gibes, the wagging of heads, how shall she bear all these? And besides, that step would be final proof that I am a dissolute, a long-standing unbeliever, and that in vain I have misled all those who know me, letting them think me faithful to God and to His holy ones. Why else should I have taken such a sudden step? This proof, which would be public knowledge, would be difficult for my mother, most difficult. So everything would be lost, everything: “This one too, my son, in whom I have put all my hope, he too has become a disappointment, and so what is left for me in my life?”

So I cannot possibly take that step from here, it being so abrupt and so public. Not so if that were done from there, from Belz. My mother herself knows and senses the great difference between myself and Belz, and however much she does not know me in all respects, she knows me more than others and is therefore aware, how different I am from Belz and its life. Moreover, she is worried lest I dislike my bride, since she is not very good-looking and may also not be to my taste in other respects, and so think many other townspeople as well. She is therefore apprehensive and worried, lest I be unable to reconcile myself with Belz, and go to war there; and she, instinctively, realizes the possible results of that war... And more than once she has told me of her fears. Nevertheless, she comforts herself, in the hope that perhaps that will not happen, and I will accustom myself to Belz ways; and perhaps I shall like my bride and things will turn out for the best. But all the same, she fears the other side, the other aspect, and that step would not come to her as a surprise. And any pain, strong as it might be, would therefore not be new, it would be expected and foreseen, and so less acute, not so painful and stinging. The public aspect would also not be so obvious here [in Shpikov], for only an echo of that step would be heard here. Only fragmentary information, wrapped in secrecy, would reach our town here, insufficient to arouse such a commotion. And moreover people might find some justification for my action—“Who knows what forced him to take such a step, surely he could no longer bear it.” And the shame would not be so great, and above all, responsibility for my action would not rest with her, my mother, because I shall already have left her home. Therefore, her pain would not be so unbearable, and that would make it easier for me to take the step.

So in the final analysis, every cloud has a silver lining. Perhaps through Belz I shall be able more easily to achieve my goal, my longstanding heart’s desire, and perhaps, taking the step from there, I shall have better means at my disposal.

Such is the situation now, that is what I am doing and thus I think. Darkness surrounds me, but one spark glimmers in the darkness. I intend to fan the spark and ignite a great fire that will light my way in life; but possibly, before I am able to make it into a flame, it will flicker and die out completely, and I shall remain standing alone, solitary in the darkness. I fear that possibility, but find strength in the hope that it will not go out, that I will be able to make it into a great light, an illuminating light.

I hope, for without hope what worth is life? And out of that hope I am now about to take the first, difficult, step, of marrying into Belz.

That is my confession, the confession of my life, withered and faded before its time, the confession of my tortured, afflicted, soul, the confession of my squandered talents. I began to write it several weeks ago, but could not complete it until now. The harsh conditions of my life have brought me to this. I have been writing it for a very long time, one quarter-hour each day, and upon beginning to write I have been forced to stop midway, obliged to hide the letter for fear it might be seen by someone. Your honor will realize from my unclear writing in what state it has been written. A word here, a word there, page put together with page, until the letter was complete. Were I able to write my letter with the requisite peace of mind, it would be different, more solid and coherent, from beginning to end, one continuous narrative. But since I have not been able to do so, it consists only of disconnected ideas, fragments, convulsions of my mind. And now, if your honor should wish to reply, I beg you to reply quickly, to reach me immediately during the first week of my wedding. You may send the letter care of my sisters, and they will send it on to me.

With admiration and respect, hoping against hope for your answer,

Yitzhak Nahum Twersky

All credit for this translation goes to Prof. David Assaf of Tel Aviv University

"Grappling with the Enlightenment"? I don't see much grappling or enlightenment here. This guy is clearly deeply depressed. He hates his religion, hates his family, hates his community, hates the world, hates himself. Reminds me of a different guy we like to talk about on our blog. Too bad he didn't live in a time when therapy existed.