Frum History: Zionism (Part 2)

The innovation of religious Zionism and a short monograph on Rav Kook

(This is the second post in our series on Zionism, if you have not read the first post it is highly recommended that you do so below, if for some reason you cannot access the link, you can reply to this email that you would like it sent. You may need to click “view this entire message” in your email to view this whole post.)

Frum History: Zionism (Part 1)

This marks the begining of a series of posts on Jewish history, the goal will be to try and bring fresh perspectives to the events that have contributed to the formation of the modern frum world. Enjoy! Zionism, in some circles of Judaism a dirty word, in others it is a core identity of what it means to be Jewish. In the community I was brought up in it …

For most of Zionisms early history, we see almost complete opposition both within the religious and other non-religious camps. The secular Bundists saw the Zionists as explicitly playing into the hands of the right-wing anti-simetic movements that sought to remove the Jews from Europe. A Bund commander from Warsaw explained when asked about Zionism that “the Bundists did not wait for the Messiah, nor did they think about migrating to Palestine. They wanted Poland to be a country of justice, socialism, and equal rights for national minorities.” The Reform movement as well felt that any focus on a “restoration of a Jewish state” was anarchonistic and reflected poorly against their updated views of Judaism as a modern religious community. During the Pittsburgh Convention of 1885, the Reform movement passed a resolution stating, “We consider ourselves no longer a nation but a religious community, and therefore expect neither a return to Palestine,...nor the restoration of any laws concerning a Jewish state." The first part of this statement regarding viewing the Jewish people as a religious community and not a nation is actually parallel to the mainstream Orthodox view at the time.

As we know, most Orthodox Rabbonim viewed the secular Zionist movement with disdain, as well as believing that Zionism would supplant religion as the focal point of Judaism and replace it with nationalism. They also felt that the creation of a Jewish state would not come through the work of man but through the coming of the Messianic era. Reb Chaim Soloveichik warned of the spiritual dangers inherent in Zionism: "The people of Israel should take care not to join a venture that threatens their souls, to destroy religion, and is a stumbling block to the House of Israel.” Rav Elchonon Wasserman (1874-1941) was of the opinion that Zionism constituted Kefirah (heretical ideas) and held that “anti-semites want to kill the body, zionists want to kill the soul; it is better to die than to consort with zionists.” When the question of a Jewish state emerged in discussions during an Agudah convention in 1938, Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzinski wrote:

I received your letter from Baranovitch today. Because of my ill health, I was unable to evaluate the suggestions for the assurance of religious matters in a Jewish state, if the Mandatory government is to decide this. But my opinion is close to what you suggested when you were here. Regarding our participation in the preparation [for a Jewish state], if there really is definite information that the Mandatory government is ready to carry out partition and the Jewish state, it is proper to participate with a mesiras modaa (statement of disavowal) as we have spoken. But if it is really unlikely – as it seems from the viewpoint of our friend Mr. Rosenheim – we must consider this carefully, that it not look like a giluy daas (revelation of opinion) that we agree to the very idea of it [a Jewish state]. (Mikatowitz Ad Hei B'iyar, p. 306)

Zionism had wrecked so much destruction in the religious world that the Agudah bloc felt it better to take a stance that would completely oppose the creation of a Jewish state until it was absolutely certain that one was going to be created. In the end, we will see that this meant the religious would have very little say once the state actually did come to fruition. Before the horrors of the Holocaust and subsequent formation of the state of Israel, Zionism was faced with immense contention from the Orthodox, Reform, and secular movements within its own demographic (the Jewish people).

Where does religious Zionism fit into this picture? At this point, it seems that even the term is an oxymoron, given that Zionism was considered antithetical to the religious principles of Judaism. Well, not everyone in the religious camp thought that way. Some were able at least to see a silver lining in the secular Zionist movement or even come to view them as the process by which G-d would bring the Geulah (salvation).

The first intellectual strand in the religious Zionist worldview appears in the works of Rav Zvi Hirsch Kallisher (1795-1874), a talmid (student) of both Rav Akiva Eiger (1761-1837) and the Ba’al HaNesivos (1760-1832). He wrote commentaries on the Chumash, Gemara (Talmud), and Shulchan Aruch, as well as contributing to many Hebrew periodicals of the time. In 1862 he published a sefer called ‘Derishat Zion’ outlining key points that would later be used as the foundations for religious Zionism:

Jews should buy and cultivate land in Israel.

The founding of a school of agriculture for this purpose.

Formation of a Jewish military garrison for the security of the communities that would move there.

Money should be collected around the Jewish world for the establishment of these objectives.

The salvation of the Jews, which was promised by the Prophets, can only come about in a natural way — by self-help

This appendix of the sefer contained an invitation to the reader to join the societies that would help in the creation of these colonies. The sefer quickly gained prominence, especially in the poorer communities of eastern Europe, and was translated and reprinted multiple times.

It is the fifth point that Kallisher makes which, is where I think the line was drawn between the mainstream Orthodox and religious Zionists of the 20th century. The idea of self determination-that we should take an active role in the salvation of the Jews from exile, this is what sets them apart. It should be noted that Kallisher lived a full generation before Herzl, and his sefer and views within it are not to be confused with support of Herzls movement or having been influenced in any way by the secular world. In some ways this makes Kallisher the ‘purest’ Zionist, untainted by the secular or socialist worlds or as a reaction to growing anti-Semitism of the time like the later Zionist movement definitely was.

Now that we have our first religious figure of note, others will follow. Notable figures in the history of early religious Zionism were Rav Yitzchok Yaakov Reines (1839-1915) and Rav Shmuel Mohilever (1824-1898) both products of the Volozhin Yeshiva who studied under Rav Chaim Soloveitchik and Rav Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin (Netziv (1816-1893), they would both go on to found the Mizrahi movement in 1902 at a conference in Vilna. The Mizrahi movement held that religious Jews should take part in Zionism’s objective of creating a Jewish state and actively promoted this idea across eastern Europe. They were the first religious organization to join Herzl’s WZO and held correspondence with him. In 1929, they founded Bnei Akiva, which was a youth group aimed at furthering the goals of the Mizrahi movement, which was to synthesize a life of Torah with civic work to prepare for the settlement of Israel. No major Orthodox Rabbonim of note were in favor of the movement as they felt that any inkling of joining together with the secular movement was dangerous to leading a religious life, we will later see some change in attitude after the creation of the state.

Although Rav Tzvi Hirsch Kallisher may be considered an early proponent of religious Zionism and the Mizrahi movement a later iteration of his ideas, the full encapsulation of the movement occurred within the thought, writings, and life of Rav Kook. Rav Avraham Yitzchok Hakohen Kook (1865-1935) was the enigmatic face and leader of the religious Zionist movement of his time, and many of his ideas continue to have a large effect even today. Although he was close to many Rabbonim in the mainstream Orthodox world, he remains a polarizing figure in the Chareidi world today (see note 3). He attended the Volozhin Yeshiva in 1884 becoming a top student of the Netziv, and learning with Rav Eliyahu David Rabinowitz-Teomim (The Aderet (1843-1905) there he ended up marrying his daughter. Not only did he become a expert of Talmudic and Halchic matters, he was also a master in the nistar (hidden/mystical) parts of the Torah, having learned under Rav Shlomo Elyashiv (The Leshem (1841-1926) in Shavel, and ended up playing an integral role in bringing the Elyashiv family from Lithuania to Israel.

Rav Kook was a prolific author of sefarim, not only in breadth, writing on everything from Chiddushim (Novelle) to philosophy to Kabbalah, but also in depth. His seforim are known to be among the hardest to decipher even amidst Rabbonim that are experts in whatever field he was writing on. His thought was not without contraversy though. Rav Kook took a radically different approach to the rise of the secular Zionist movement that had occurred during his lifetime. Unlike the vast majority of Orthodox Rabbonim who could only see sin and transgression with the movement, Rav Kook was inclined to see a “spark” of the Geulah within these non-observant Jews. He felt that the very fact that this group of Jews were so bent on their intention to create a new state of Israel showed that if even on the outside they may look to be doing it for secular nationalistic reasons, it was their very Jewishness and inner love for Klal Yisroel (Nation of Israel) that drove them forward.

He believed that the movement to create the state of Israel was part of the national rebirth of Klal Yisroel and the steps being taken in its direction marked the Atchalta Degeulah (The beginning of the redemption), This was a completely novel approach to the Zionist “problem”. Instaed of viewing them with fear and contempt, he was able to see a motive that not only gave them his approval but it placed their doings at the highest spiritual level as well! Much of this perception, while clearly coming from a deep love of all Jews, was clearly influenced by Rav Kook’s Kabbalistic cosmology wherein the world is filled with various Klippoth (husks) that contain spiritual light to be wrangled from within them1 .

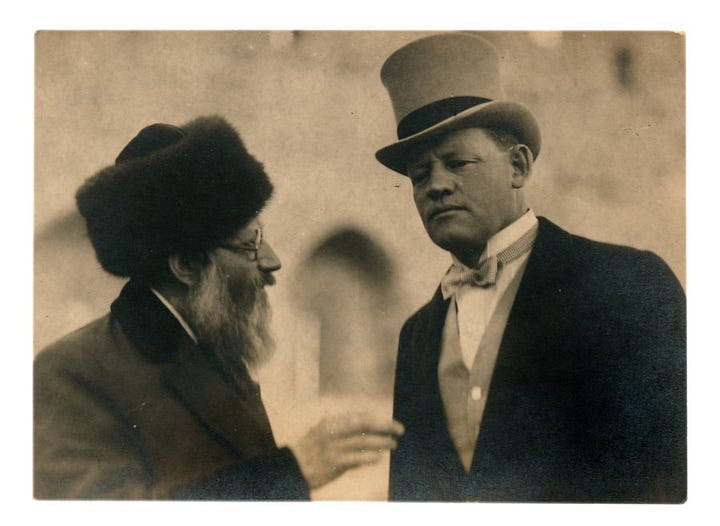

Needless to say his approach was not wholly accepted within the Orthodox world. Many felt he was giving in to the popular Zionist viewpoint of the time. It was especially his empathy that he held towards the more secular elements within Judaism that arose the suspicion of those Rabbonim. Rav Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, although a great admirer of Rav Kook and someone that he took great pride in having a personal relationship with was taken aback when Rav Kook accepted the position of becoming the first chief Rabbi for the Rabbanut of Palestine under the British Mandate in 1921. There was fierce opposition to Rav Kook within the old Yishuv (settlement) in Meah Shearim. They had no affinity for Rav Kook’s seemingly soft views on the secularists and saw him as a threat to their long-established way of life. This rift aided in the formation of the Edah HaChareidis (Congregation of Hareidim) which exists to this day as wholly opposed to the state of Israel2.

Rav Kook had some reservations about the Mizrahi movement as well and felt that they had tempered the religious spirit in deference to the Zionist one:

The Mizrahi movement must take responsibility and repair this weakness of faith, and in doing so revive the great spirit of Kedusha (Holiness) that is waiting to influence the Zionist movement. (Trans. from Ma’amrei Hare’iyah)

As well as taking an extremely nuanced approach as to why Zionism was overidden by the secular and had not been the advent of the religious:

The knowledge that everything is in the hand of God and for a higher purpose, and the promise that we will return to our foundation, our holy land, is itself what has weakened our practical effort and caused a deadening of enthusiasm. As long as there are opportunities to act, there is no reason to be passive, for are not all acts of man in truth acts of God? Nevertheless, the arrival at this understanding requires much preparation and maturing in intellect, in feeling, and in life. We also need to greatly arouse the desire that we ourselves will be the ones to act, as much as we possibly can.

But we have fallen, and we have not risen up. So what does God do? He strengthens the chutzpah b'ikva d'Meshicha (audacity in the times of the Mashiach, Mishnah Sotah 9:15) so that the masses distance themselves from the depths of knowledge and faith, overstepping all boundaries until the awareness of God within them is silenced. Consequently, the faithful promise of God does not inspire them. Instead, their yearning comes from the longing for comfort from their present persecutions, and even, to a small degree, from the drive to defy faith, Torah, and mitzvot. Nevertheless, this motivation will do its job to ignite their hearts and cause them to move and to act.

In the meantime, those who are religious need to develop an understanding of the holiness of practical actions until all souls can be uplifted with this knowledge. That which has been accomplished on the basis of forgetting God will then be accomplished even further through awareness of God's desires.

(Trans. from Pinkasei Hare’iyah pp. 143-144)

Rav Kook felt that the evolution of Israel from an ethno-religion into a nation-state was a crucial part of the Jewish identity but since the religious had given up hope on any practical efforts towards its creation, G-d “had” to use the nationalistic spirit of the time to make it happen. This is in sharp contrast to the mainstream Orthodox view of the time, which believed that not only would the creation of Israel not come through secular means, but would not come through any practical effort on our part at all!

It was ideas such as these which lead Rav Kook to recieve much criticism from within the religious camp. Many were of the opinion that his ideas were too lofty to be practical and therefore should not be put into practice even if they were indeed correct. It is worth pointing out that Rav Kook was not isolated during his lifetime from the mainstream religious world, on the contrary both Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer and Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstien in a letter of support for their classmate (both studied with Rav Kook in Volozhin) who was then coming under attack from members of the Edah Hachareidis referred to Rav Kook as “Our honored friend, the great gaon and glory of the generation, our master and teacher, Avraham Yitzchak Hacohen, shlita”. Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzinsky who we have seen was not a friend of Zionism also referred to Rav Kook in a letter as “My Dear Friend, Ha-Rav Ha-Gaon, Ha-Gadol, the Famous One... The Prince of Torah, Our Teacher, Ha-Rav Avraham Yitzchak Ha-Cohen Kook Shlita...". So it seems that although he held views that were considered eccentric within the Orthodox world to say the least , he was highly respected by major figures in the mainstream Orthodox world at the time3.

Rav Kook was also a trailblazer in the world of Kiruv which was a completely novel idea at the time. He spent time in Isarel traveling to the secular Kibutzim trying to garner more religious observance amongst the settlers. Within the frum world little had been done to reach out to the many that had fled the ghetto walls once the doors were flung open by the winds of enlightenment. Rav Kook felt that even Chassidus which was created to speak to the unlearned Jew had failed in inspiring the masses towards religiosity:

Our collapse has come about not because rabbonim do not protest against the institutions of atheists that are destroying the holy land, but because they only protest, and nothing else. We are being forced to admit that even Chasidus, which was meant to reveal the divine light in every heart and mind, has changed its character. Today it is heading only in the path of an unsophisticated fear. Indeed, there is very little difference between the Chasidim and the Misnagdim [nowadays] (Non-Hassidic Orthodox Jews). (Trans. from Igros Hare’iyah)

Rav Kook was a fascinating figure in the story of religious Zionism4, and although he did not live to see the creation of Israel, he was convinced that it was not far off and was willing to make the necessary preparations for it, both on a physical and religious level. This separated him from many of the mainstream Rabbonim at the time who were attached to the idea that no state would be supported if it was not fully founded on Torah principles, not willing to make any concessions to the Zionist movement. Unfortunately this meant that the frum world was not well prepared for the events of 1948. Rav Kook was able to circumvent much of the theological heartache by integrating the creation of Israel into the idea of a slowly revealed redemption. Whether you agree with everything he said or not, this was a masterful innovation that has had a lasting impact untill this day.

I am in no way an expert in Kabbalah and am only giving a brief sketch for reference, there are people that spend their lives trying to understand these ideas.

The politics of the Edah HaChareidis and its formation are a very complicated matter.

See Rav Eitam Henkin’s H’YD posthumously published work “Studies in Halackha and Rabbinic History” for accounts of various attempts to cover up Rav Kooks reverence and influence by censoring letters and haskomos (recomendations).

See Yehudah Mirsky’s “Rav Kook: Mystic in a Time of Revolution” for a complete account of his life that sticks to the facts but is not too academic.